Ten years after MH17: BZ staff share their memories of the disaster

Weblogs

On 17 July it will be 10 years since the downing of flight MH17 in eastern Ukraine. All 298 people on board, including 196 Dutch nationals, died. Dozens of staff members of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were involved in dealing with the aftermath of the disaster. Some helped with the recovery of the victims. Others were involved in the Netherlands’ efforts to achieve justice, in their capacity as diplomats. The disaster will always stay with them: ‘It got under my skin.’

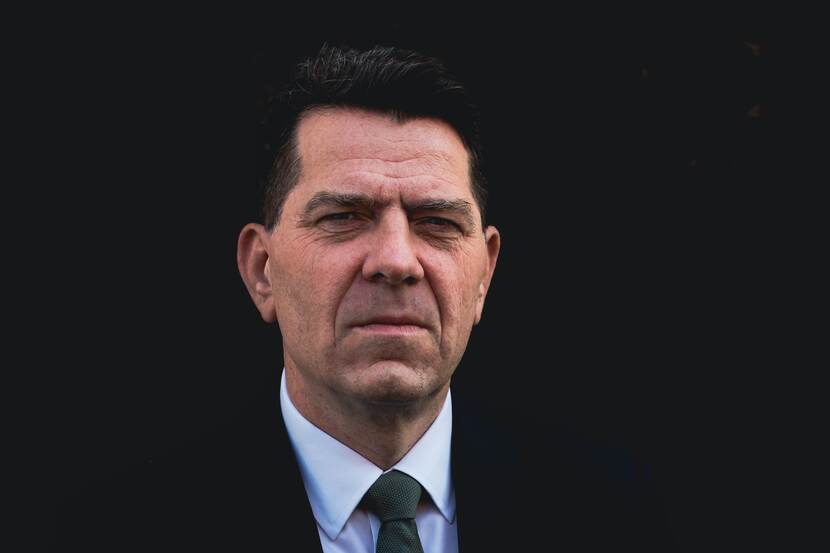

When the report came in, on that rather cloudy summer’s day on 17 July 2014, the seriousness of the situation was immediately clear. A civilian aircraft that had departed from Schiphol airport was shot down in eastern Ukraine. The wreckage had landed in wheat fields near the village of Hrabove, where heavy fighting was going on between the Ukrainian army and pro-Russian separatists. ‘It was a minefield, in more ways than one,’ says Michael Pistecky, who had started work as a Ukraine policy officer in May 2014.

Crisis teams

Crisis teams convened that same day, both at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and at the embassy in Kyiv, the latter led by chargé d’affaires ad interim Gerrie Willems. Robert Dresen, team leader for Russia and Central Asia at the time, helped the crisis team in The Hague monitor political developments in the region. Every few hours, the team issued a bulletin with updates.

‘It was clear from the start that this was a crisis that would require a lot of stamina,’ says Mr Dresen. ‘On the one hand we had to respond quickly, for instance in terms of dealing with the separatists in the area, so that the bodies of the victims could be repatriated. On the other hand, we had to be mindful of the diplomatic consequences of such contacts in the longer term.’

‘When flight MH17 was shot down, the war in Ukraine suddenly reached the Netherlands.'

On 18 July, dozens of extra desks were brought into the embassy in Kyiv, Anneloes Viveen recalls. She was deputy head of the embassy’s economic affairs section at the time. ‘Dozens of people came from The Hague to boost our numbers at the embassy. That was needed, and it was great. The whole embassy had already been in ‘crisis mode’ since November 2013, when large-scale protests erupted in Kyiv against President Yanukovych.

Those protests continued until the Maidan Revolution in February, which led to the ousting of the president and the fall of his government. A month later Russia annexed Crimea, and a few weeks after that the war in eastern Ukraine started. ‘When flight MH17 was shot down, the war in Ukraine suddenly reached the Netherlands,’ Ms Viveen says. ‘But the embassy had been reporting every day for months already on the latest political and security-related developments.’

Repatriation and investigation

The top priority in the immediate aftermath of the disaster was the repatriation of the victims’ bodies. And an investigation was launched by the Dutch Safety Board. Hans van de Ven was working as defence attaché at the embassy in Kabul in July 2014.

‘I was on an official trip to Pakistan when I got a call asking me to go to Ukraine. Twenty-four hours later, I arrived in Kyiv. My assignment was to repatriate the victims’ bodies and personal belongings, and lead the recovery team.’ The fighting in the area made it a highly complex task, in terms of both logistics and diplomacy.

'I was on an official trip to Pakistan when I got a call asking me to go to Ukraine. Twenty-four hours later, I arrived in Kyiv.'

‘Purely practical’ contact with the separatists

Mr Van de Ven adds: ‘Thanks to the OSCE, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, contact had already been made with the pro-Russian separatists. In my capacity as a civil servant, I also had talks with the separatists, together with the OSCE. They were purely practical discussions: about the route into the area, when we would start our work – that kind of thing.’

Preparations for the repatriation of the bodies were in full swing, but in the Netherlands there was mounting criticism. There was a sense that the recovery had started too late, and that the work at the crash site in the first week had been carried out poorly by the local fire brigade. Both Hans van de Ven and Anneloes Viveen dispute this. Mr Van de Ven says: ‘Not everything went perfectly, but I felt – and still do – that under the circumstances the recovery operation was effective and well organised. The mission worked hard on this, together with the Ukrainian authorities. Ukraine, for instance, arranged a refrigerated train to take the victims’ remains to Kharkiv.’

The Ukrainian authorities were engaged and cooperative from the outset, Anneloes Viveen says. ‘That’s quite remarkable, especially when you consider that Ukraine was initially suspected of possible involvement in firing the fatal missile.’ The Ukrainian people took the Netherlands to their hearts. Every day, Ms Viveen and her colleagues encountered an ever-growing sea of flowers and soft toys at the entrance to the embassy in Kyiv. ‘It was touching and showed great empathy – even as war had been claiming so many Ukrainian casualties over the months.

Proud of his team

Hans van de Ven didn’t return to the Netherlands until spring 2015. At the height of the operation, the recovery team comprised 700 people. They painstakingly searched the now bare wheat fields near Hrabove for remains, personal belongings and pieces of wreckage. Every inch of those 70 square kilometres was searched. ‘I’m proud of what we did there as a team. Unfortunately, two of the Dutch victims were never identified. I still think about how awful that must be for their families.’

After the initial crisis phase, Michael Pistecky worked on the MH17 disaster for years, first as a Ukraine policy officer and later for two years as head of the MH17 task force. Working with legal experts from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Justice and Security, he helped conclude an agreement between the Netherlands and Ukraine that would make it possible to prosecute the perpetrators in the Netherlands. That agreement, signed in Tallinn, didn’t make the front pages, but its importance has since become clear. ‘The disaster got under my skin. For four years, we hardly had any kind of private life. That’s just the way it was. All that hard work was in order to achieve justice, for the victims’ families in particular. Everyone who worked on this case felt that responsibility.’

‘The disaster shaped our policy with regard to Russia. Truth, accountability and justice became our top priorities with regard to MH17.’

Russian responsibility

By the end of 2014, Anneloes Viveen was organising Dutch trade missions to western Ukraine again, far away from the front in the east, and far away from the MH17 crash site. She still thinks about the disaster often. To her it is only one of many tragic moments in Ukraine’s recent history. ‘It planted a seed in me that grew into a desire to help Dutch nationals in distress around the world – as I do in my current job as consular crisis manager.

Robert Dresen left the basement housing the crisis team in September 2014. As team leader for Russia and Eastern Europe, he remained involved in the aftermath of MH17, leading the MH17 task force from 2018 to 2019. ‘The disaster shaped our policy with regard to Russia. Truth, accountability and justice became our top priorities with regard to MH17.’

‘Our plan was to establish a UN tribunal to prosecute those who shot down flight MH17. But Russia dismissed the plan.'

On 5 June 2015, a Dutch delegation visited Russia for the first time to discuss MH17. In an ornate room in Moscow, foreign minister Bert Koenders, the Dutch ambassador and Robert Dresen sat opposite their Russian counterparts, including Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov. ‘Our plan was to establish a UN tribunal to prosecute those who shot down flight MH17. We wanted to convince Russia that this was a good idea.’ But Russia dismissed the plan. Three years later, in May 2018, the Netherlands and Australia officially held Russia responsible for the downing of flight MH17. Robert Dresen was at the session of the UN Security Council in New York where then foreign minister Stef Blok explained that decision. ‘Those were key moments.’

Justice and redress

Dealing with the aftermath of MH17 was an experience that is etched into everyone’s memory. ‘We were working for justice and redress for the next of kin,’ says Michael Pistecky. ‘It gives you an enormous sense of purpose and unity. Everyone was working with so much focus. Not just at the foreign ministry, but throughout the Dutch government. Robert Dresen also vividly remembers those first weeks in the crisis team. ‘They were long days: I arrived and left in the dark, even though it was the height of summer. Everyone was running on adrenaline. After three weeks, we had to take a break. You’re working so hard as a team, you really end up in overdrive. And you can’t keep that up for too long.’

Everyone involved has particular moments they will never forget. Especially the day the victims’ bodies returned to the Netherlands – 23 July. The most emotional moment for Michael Pistecky was the day in June 2018 when the Netherlands officially held the Russian Federation responsible for downing the aircraft. ‘For me, it all culminated in that one day.’

Ten years after the disaster, MH17 is still very much a focus of attention. Not just in the Netherlands but internationally too. Robert Dresen thinks that is quite remarkable. ‘It’s partly due to the context in which the disaster took place. But I also consider the international attention to be a result of the resolution that the Netherlands submitted to the Security Council shortly after the disaster. We called for truth, accountability and justice.

That might sound a bit obvious, but it has proven very important. But I don’t want to make us diplomats sound more important than we are. To my mind, the real heroes are the people who recovered the victims’ remains in eastern Ukraine. And most important of all are the families of the 298 people who lost their lives. Achieving justice is very important for the Netherlands, but for them it’s nothing short of essential.’